What’s happened to Inflation?

Why are we not seeing the price inflation that we might expect after six years of central-bank credit creation? This is a puzzle that many economists have been debating since the US Federal Reserve, followed by the Bank of England, and to a lesser extent the European Central Bank, began the process known as quantitative easing, or QE, immediately after the financial crisis.Although it doesn’t actually involve printing money, QE amounts to creating credit, which is effectively money, out of nothing, and using this credit to buy government bonds (or debt) from private financial institutions. The plan was to stimulate the economy by keeping down interest rates and also to provide funds to the struggling banks so they could lend it out. The stimulus worked to some extent, and the money probably saved a few banks from collapse, though lending didn’t increase much because there wasn’t a great demand for even more debt – most people had learnt that lesson, and were now poorer.

One might question the morality of using public money to save private banks, effectively transferring billions from the taxpayers to the bankers, the same people that had wrecked the economy in the first place. Some have called it robbing the poor to give to the rich, and this is not far from the truth – though perhaps it is mostly robbing the middle classes to give to the rich.

But the issue I want to address here is inflation. It was predicted by many economists, especially those who believe in ‘sound’ money (myself included), that all this credit creation would lead to rising prices. After all, it’s a simple economic rule that printing money beyond the amount warranted by real economic growth must devalue the currency and therefore lead to higher prices, and in the US the annual rate of excess money growth, from 2008 to 2013, was around 5%. So where’s the price inflation?

I think there are two aspects to this puzzle:

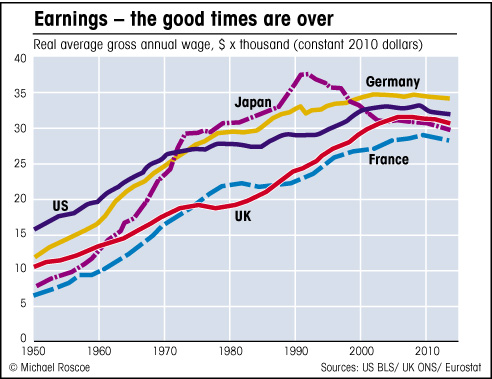

For one thing, hardly any of this new credit is finding its way into general circulation – the rate that money is being spent (its velocity) has fallen significantly since the artificial boom years. Although the intention of governments was to boost lending in a vain hope of re-igniting the consumer-spending bubble, this isn’t happening – the majority of consumers understand that their real earnings are not increasing, and in many cases are falling, and therefore they can’t afford to get into more debt.

The new money has gone into the banking system, and there it has stayed, inflating only bank reserves and stock markets.

Leading on from this, because most people’s earnings are static or falling, demand for goods and services remains subdued, thus keeping down prices – there is still an excess of supply left over from the boom times. Unfortunately for the producers, this is likely to remain the case for a long time, because the excess demand was artificially created during the credit bubble, and most people (though perhaps not our leaders) have learned that lesson.

The second aspect to this lack of price inflation is less obvious and more theoretical, but I think we might have entered a new phase in global economics, brought about by the fact that China, the world’s great manufacturing centre, keeps its currency, the renminbi (or yuan), more or less pegged to the dollar (and recently to other currencies too, through a ‘basket’), even though its economy is performing very differently to the US economy, with much higher growth but also much higher inflation.

We have a situation whereby China, along with other big emerging economies such as India, is keeping wages down, and this effect is gradually becoming more global. If wages are falling and prices are rising slightly in nominal terms, by one or two percent, we might have a situation where prices are rising by four or five percent relative to the average wage of the majority, factoring out the richest 1%, who are in a different situation due to distortion by the financial sector, as I explain below.

And because none of these levels are absolute – ie, all prices are relative to each other – we might need to rethink the way we view this relationship between wages, prices, interest rates and GDP growth. Zero might not be the real baseline, as it were, and we might be experiencing greater price inflation than we realize.

To come back to the increasing inequality between the top 1% (or wherever we might draw the line) and the rest of us, this is a function of the difference between those who can benefit from all the cheap government money that has been flooding the financial markets but not feeding through into the real economy, and those who rely on wages or benefits, both of which have been falling relative to prices.

The rich use cheap money to make more money through asset buying and speculation, while the rest of us pay the price in job losses and falling wages. In this way, the inflation shows itself in asset bubbles rather than rising retail prices, which are kept down by cheap labour. So the great majority of people in the world have in fact been experiencing inflation, but in the advanced economies it isn’t showing up in the figures for consumer prices, because it’s a result of falling incomes rather than nominally higher prices.

This argument is boosted by a recent report from the US Federal Reserve, which shows that … ‘only families at the very top of the income distribution saw widespread income gains between 2010 and 2013 … Families at the bottom of the income distribution saw continued substantial declines in average real income.’

We’d become accustomed, during the boom years, to a situation in which inflation was fed by rising wages, as workers demanded rises to compensate for higher prices – the process was self-perpetuating, a result of a booming economy. But the real economy is no longer booming in the more developed nations and isn’t going to, because the process of development under the capitalist system involves ever-increasing productivity, which cuts jobs and holds down wages, especially in the globalized marketplace.

So the official consumer price index becomes less and less reliable as a guide to what is really happening in today’s world. There is also the complicated relationship between money supply, interest rates and expectations of inflation, which is a factor that can lead to actual price inflation (people might spend rather than save, producers raise prices, and so on).

These expectations might depend on national circumstances, including recent history. For example, in countries that have been experiencing low inflation for some time, such as most advanced economies these days, monetary expansion can exist with low interest rates because inflation expectations are low, whereas in regions that have experienced high inflation, rates must rise to compensate for the expected price rises.

So there are several answers to the puzzle of low inflation:

1) The newly-created money has remained in the banks, rather than entering the real economy – we see inflation of share prices, but not consumer goods. (Another way of putting this: the excess money isn’t getting into the pockets of the majority, it’s only going to the rich.)

2) Demand has remained low because most people are earning less, so supply still outpaces demand.

3) The gap between wages and prices is rising, but mostly because of falling wages rather than higher prices – in the end, prices are always, above all else, relative to earnings.

4) Expectations are still low.

RETURN TO HOMEPAGE