Living in a cut-price world

As I explain elsewhere, the globalization of wages is holding prices down, while lower earnings are limiting demand for resources. Because many commodities are of finite supply, and are gradually being used up, one would expect prices to keep rising, especially as the global population is still rising.

But a current excess of supply over demand is keeping commodity prices down, especially oil, the biggest source of wealth in this world.

In the real economy, where most people have to work for a living (as opposed to the fortunate few who get rich off the earnings of others: the rentier class, or the 1%), this globalization of prices results in lower earnings. This is a continuation of the tendency inherent to capitalism, through its encouragement of intense competition, to produce goods at the lowest possible price, even if the social cost is really very high. Cheap goods are the end product of the free-market capitalist system, its only real purpose (along with making profits, of course).

And with the rise of the internet, and digital technology generally, this process is accelerating. When we pay less for goods and services, as happens with everything from buying stuff on Amazon or eBay to sending messages and photos for free via email, social media, and so on, plus all the other outlets where intense competition is keeping prices as low as possible – the rise of the discount stores, for example – this reduction in our spending must translate into a reduction in our earning capacity, because ultimately all trade is an exchange of labour.

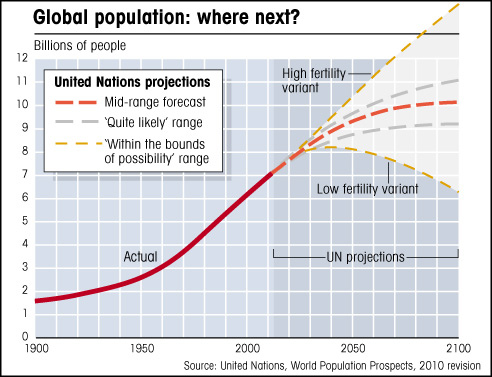

Put simply, the supply of labour globally is greater than the demand. The supply of people is rising, while the need for workers is ever decreasing, due to productivity improvements brought about by new technology.

Even in regions that are now experiencing a reduction in the working-age population, such as Europe and Japan, there is no shortage of workers – Europe has high unemployment, in fact, and Japan has been following the western trend of exporting jobs to lower-wage countries.

I think we might be entering a new phase in economic development in advanced societies, one that sees a fall in demand due to the reduction in the earning power of the majority, who stop buying a lot of the stuff they used to buy in the boom times, much of which they never really needed anyway: all the little luxuries that a once-affluent consumer society produced.

This holds down economic growth and therefore results in a vicious cycle of reduced earnings and revenues, encouraging both households and governments to borrow more to get through ‘difficult times’, though in fact things are only going to get worse: it was the boom times that were anomalous, not the tough times.

We need to accept and adapt to the end of growth, even welcome it, because the world can’t keep growing forever. We need to re-evaluate our concept of prosperity and change our economic system to one that isn’t reliant on intense competition and continuous debt-fuelled growth.

Why it’s bound to get worse

Factor in the rising inequality, where the wealthy 1% grab ever more of the limited supply of wealth, then it’s no surprise that the majority in the developed world are seeing a fall in earnings. In fact, it’s inevitable.

The only way that more and more people could be earning more and more wealth would be if the industries of the world kept on producing more and more stuff, well in excess of population growth, and if the proceeds of all this industry were being distributed reasonably evenly, via well-paid employment, throughout the world’s population.

The first of these charts (below) shows how industrial production has indeed outpaced population growth over the last sixty years, as we would expect. It shows both the post-war boom and the boom that raised the wealth of China and other emerging nations over the last two decades. But the rate of increase is slowing down, and this trend is likely to persist, as wages are held down by a shortage of jobs.

The second chart shows the relationship between industrial production and GDP, which has grown much more than production due to the accumulation of wealth and the subsequent boom in credit, or debt, as the wealthy use their money to make more money. In fact, as I explain in my book (see chart on this page), the credit bubble shows up as the growth of GDP in excess of the growth of real industry.

On both of the above charts, the green line shows total global extraction of natural resources by value, natural resources being the raw material of all the world’s wealth creation. We see how this corresponds to around 40% of the total value of production, the additional value being added by the industrial process. These are annual production figures, whereas the GDP figure represents all economic activity, including the recycling of past wealth and even credit issued by banks, which actually contributes to GDP, even though it must be repaid from future earnings. In other words, GDP figures grossly inflate genuine economic activity.

While on a global scale, industrial production has continued to rise, the proceeds are certainly not being distributed evenly. Quite the opposite – a disproportionate amount goes to rich Americans, for example, as explained here.

This situation is obviously unsustainable, for both ecological and economic reasons – producing ever more and more stuff is adding to global warming and will ultimately make the earth inhospitable for billions of people, while increasing inequality is in the process of wrecking society and must inevitably result in the failure of the capitalist system, as the majority get poorer and the growth that the system depends on fizzles out due to lack of demand, while the huge debts already owed (and still increasing) are never paid and the financial system implodes, like the giant Ponzi scheme that it resembles.

It’s the wage that really matters

All prices are relative. But how do we arrive at prices? Which price comes first? We can get a better understanding of the pricing process if we leave out money, which is really just the medium of exchange.

In the original marketplaces, people traded the fruits of their labour in a process of barter – a chicken for a pot, for example, or a basket of apples for a coat. In a vague sort of way, agreement was reached as to the relative values of these commodities, based on the amount of time and effort that had gone into their production. While the process has become much more complex, and we mostly use money instead of direct barter, the principle hasn’t really changed. So any exchange in the marketplace is fundamentally an exchange of labour, and following on from this, money ultimately represents this labour.

It’s because of this basic premise that excessive wages, especially for the kind of useless jobs we often find in the financial sector, some of which are actually destructive in terms of social and economic value, can’t possibly be merited. Very high incomes can never be truly ‘earned’, and this is why inequality is so bad – it is really a form of theft, with the wealthy taking money from those who have actually earned it.

There is an agreed average price for ‘socially necessary’ labour (to quote Marx) that is arrived at by the market-trading process, and which is constantly changing. This price includes past labour, such as that used to make tools or work the soil, and is reflected in the market price of goods. By ‘socially necessary’ labour, Marx meant that not all labour has the same value, because there must be a demand for the goods or services produced. This is why prices vary according to supply and demand – value is a function of rarity and desirability.

This process has become severely distorted by the influence of unevenly accumulated wealth, which is why financial capitalism doesn’t work – the wealth is not being distributed according to the social value of labour, but goes to the wealthy through non-productive ‘rents’ (meaning unearned income, such as interest payments, property rents, etc). Because the wealthy investor is interested only in making more money from his money, often through speculation, his activities are without social value and, apart from the 20% or so of investment that goes to real industry, are mostly destructive, because they take money from those who earn it and those who need it and give it to those who don’t need it and who will try to gain from it, thus feeding the growth in inequality.

This inequality is wrecking society, but my main point here, to come back to prices, is that the wage, or price of labour, is the origin of all prices, and this is the fundamental reason why prices are not rising anymore – the price of labour has been driven down by a global glut of workers, relative to demand.

Cheap labour and low prices go together, two aspects of the same capitalist trend: we are living in a cut-price world. As for the price of money, low interest rates mean that is cheap too, but cheap money no longer results in rising prices because the falling price of labour is a stronger force, pulling the opposite way.

RETURN TO HOMEPAGE