Most people, including some wealthy people, seem to understand that extreme inequality must be a bad thing. Those who don’t tend to advocate a simplistic kind of free-market viewpoint in which they claim that rewards are always justified in some way, because the market is always right: high incomes are always earned; billionaires are a boon to the economy; a rising tide lifts all boats, and so on.

Such justifications for extreme inequality seem unconvincing to the majority, but even so, it is not a topic to which most people give much thought, because inequality is not something we really notice in our everyday lives. We might see flashy symbols of wealth quite often, but that is not the same thing: the true extent of inequality is hidden from view.

If more people understood the reality, the detrimental effects inequality has on the national economy and therefore on their own lives – just how wrong those free-market justifications are, in fact – they would surely feel more strongly about it.

It is a subject that makes the news now and then, of course, but not in a way that changes anything. For example, a recent report showed that senior executives at Britain’s biggest corporations (those that make up the FTSE 100) were paid on average around £3.8 million per year, which is over one-hundred times the median wage paid to Britain’s full-time workers (£34,960, as of December 2023).

Similar reports appear in the news every year, without any obvious impact: the rich keep getting richer, while the majority muddle along and the poor stay poor.

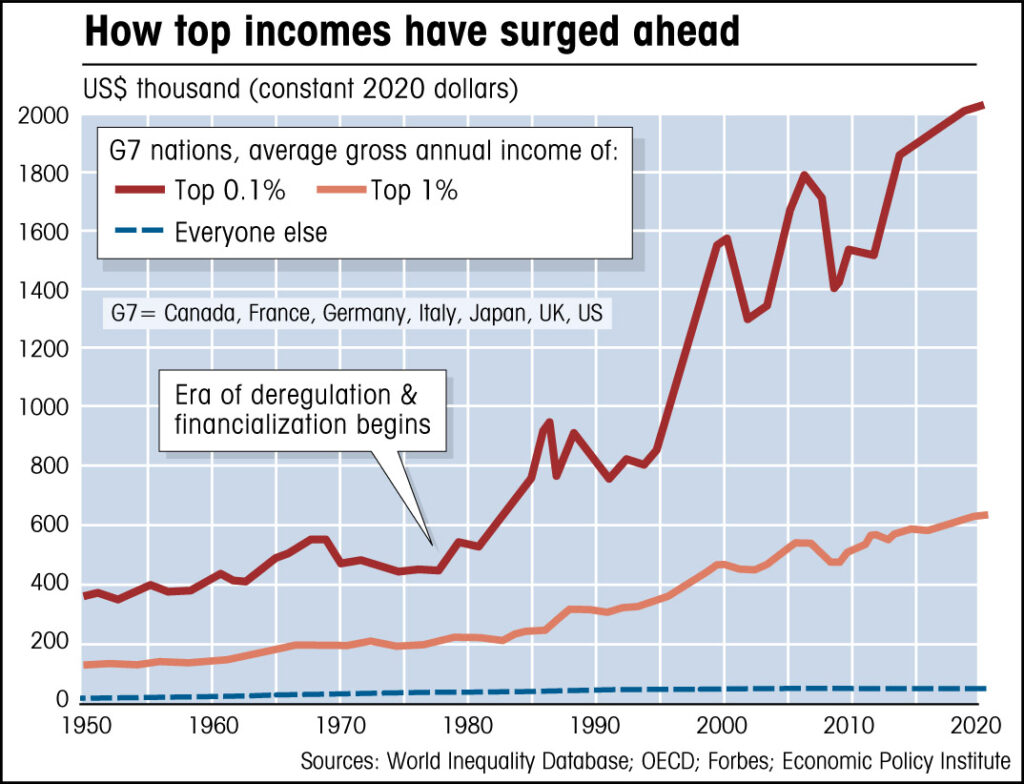

The following two charts illustrate this trend. The first shows the huge gap that has opened up, since the financial deregulation of the 1980s, between the highest paid and the rest of us. (Those senior FTSE executives, not surprisingly, are in the top 0.1%).

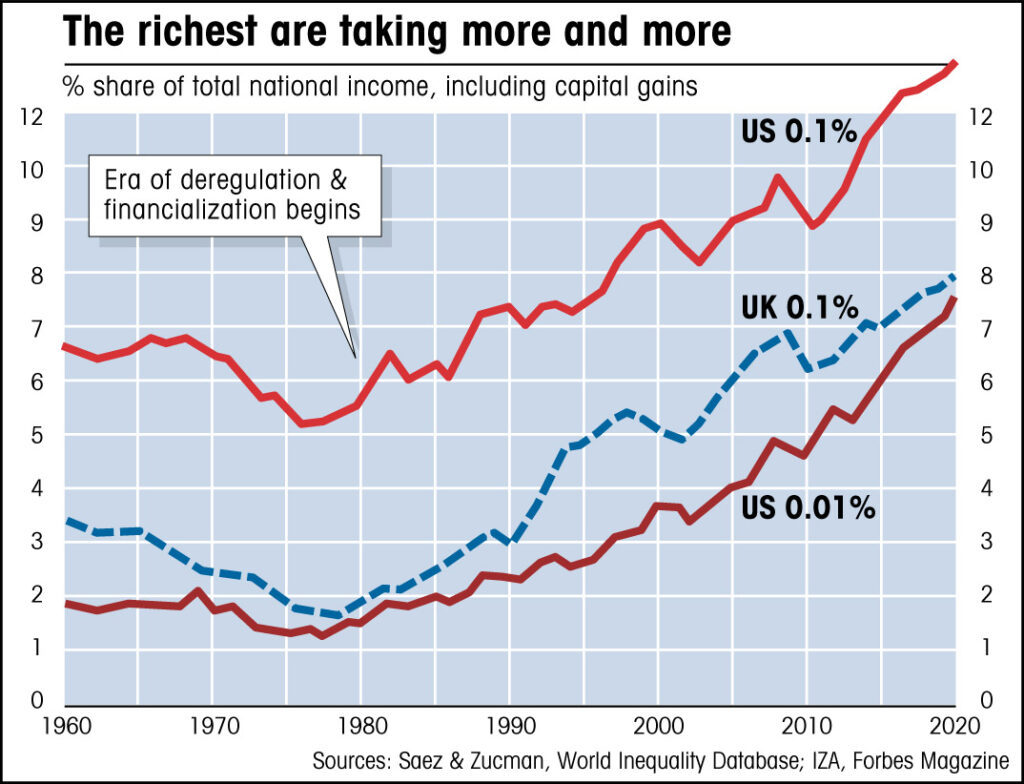

My next chart shows how the US in particular is even less equal than the rest of the G7 nations, but it also shows that Britain has been following a similar trend to the US. Indeed, this is one of the arguments made by the FTSE bosses themselves: that they need these inflated salaries to compete with American firms for the best talent. (Because the best talent is so greedy that £3.8 million per year is not enough, obviously.)

So, we might ask, do those corporate executives work a hundred times harder than the average worker? The long answer to that question runs to several chapters in my book, but here is the short answer: No, they don’t.

The reason it takes several chapters to explain why the rich haven’t really earned their wealth is that one needs to fully understand the relationships between work, wealth and money; to see how these fundamental elements of the economy fit together; how they affect our lives in critical ways. It’s a subject I’ve been investigating for a long time now, both as an FT journalist and more recently as an economics researcher and author. In my book, I make the following points and explain why they must be true:

• Incomes tens or hundreds of times the median wage can never truly be earned.

• The ‘free market’ is never really free – it is distorted by unearned wealth – and consequently it often sends the wrong price signals, especially when it comes to rewarding financiers and speculators.

• A highly unequal distribution of wealth is bad for most businesses, bad for the prospects of the majority, bad for the environment and, it obviously follows, bad for the nation as a whole.

• One reason it is bad is this: because the rich are getting richer without earning their over-inflated incomes, they must be taking wealth from the real workers, the ones who are creating the wealth.

• Contrary to the tired old arguments of the free-market advocates and right-wing generally, taxing higher incomes at a higher rate would be good for the economy and for the nation. We don’t need to placate the rich: let them flee to their tax havens; we’ll be better off without them.

On this last point, I give a detailed explanation as to why this must be so: why we don’t need the rich or their money. (It involves an investigation into the relationships between work, wealth, money and values, along with an understanding of money creation in the modern economy: the fact that money in itself has no value and can be replaced for free.)

Linked to all of these points is another simple fact: Over 90% of so-called ‘investment’ is unproductive (as explained here), so when the rich make money from their money rather than from real work, as they do most of the time, then their gains must ultimately come from the rest of us: the workers who are actually creating the wealth but are not being paid the full value of their labour; the people who are forced to pay higher rents; homebuyers who must pay inflated prices for property, etc.

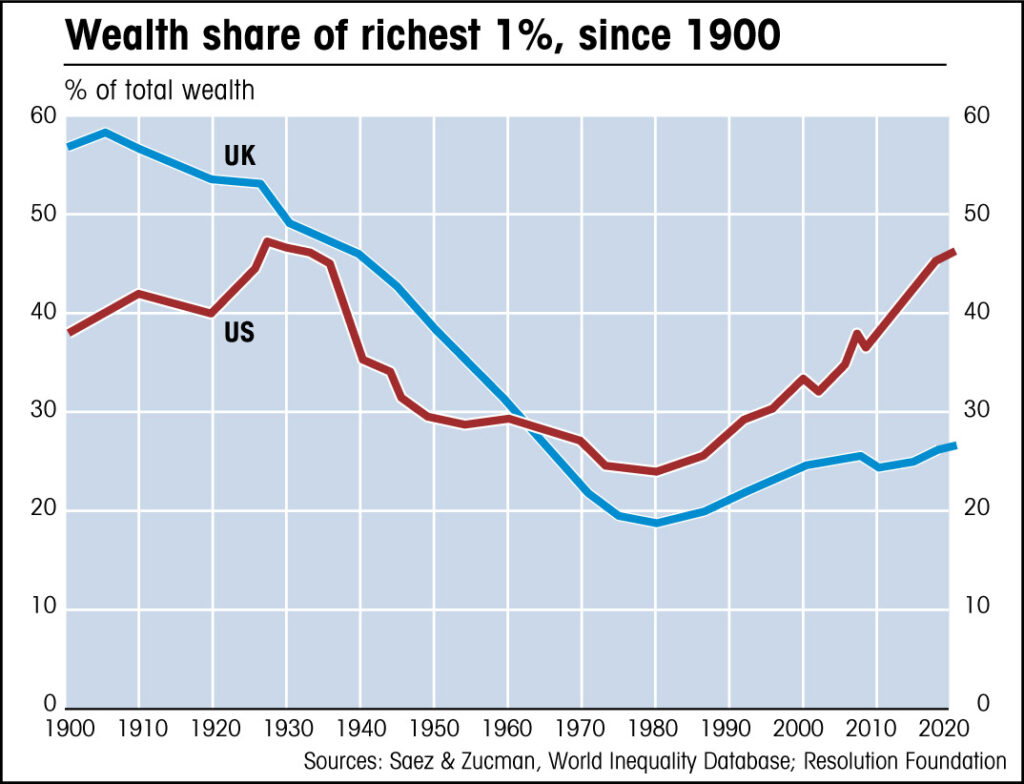

The following chart shows how wealth inequality declined in both Britain and America from the peaks of a century ago, until the government policies that helped to bring about that trend were reversed around 1980. This is the point at which the ‘greed is good’ mentality took hold in the UK and US – the beginning of the tax-cutting Thatcher/Reagan era – and since that time wealth inequality has grown again, fed by the fact that government policy has enabled, and even encouraged, the rich to make money from their money.

Governments did not intend that this further enrichment of the wealthy should be to the detriment of everyone else, of course: this outcome results from a misunderstanding. Free-market ideology convinces policymakers that encouraging the rich to get richer will lead to wealth ‘trickling down’ to the less fortunate. That this has not been happening is becoming more and more obvious; though the reasons it hasn’t happened are perhaps less obvious.

But as I said, if the rich are getting richer primarily through speculation and asset-price inflation, rather than through genuine investment in productive industry, then it is not surprising that, because they are not creating new wealth, their gains must be at the expense of society in general. In other words, the 1% gains and the 99% lose out.

See about page for contact details.