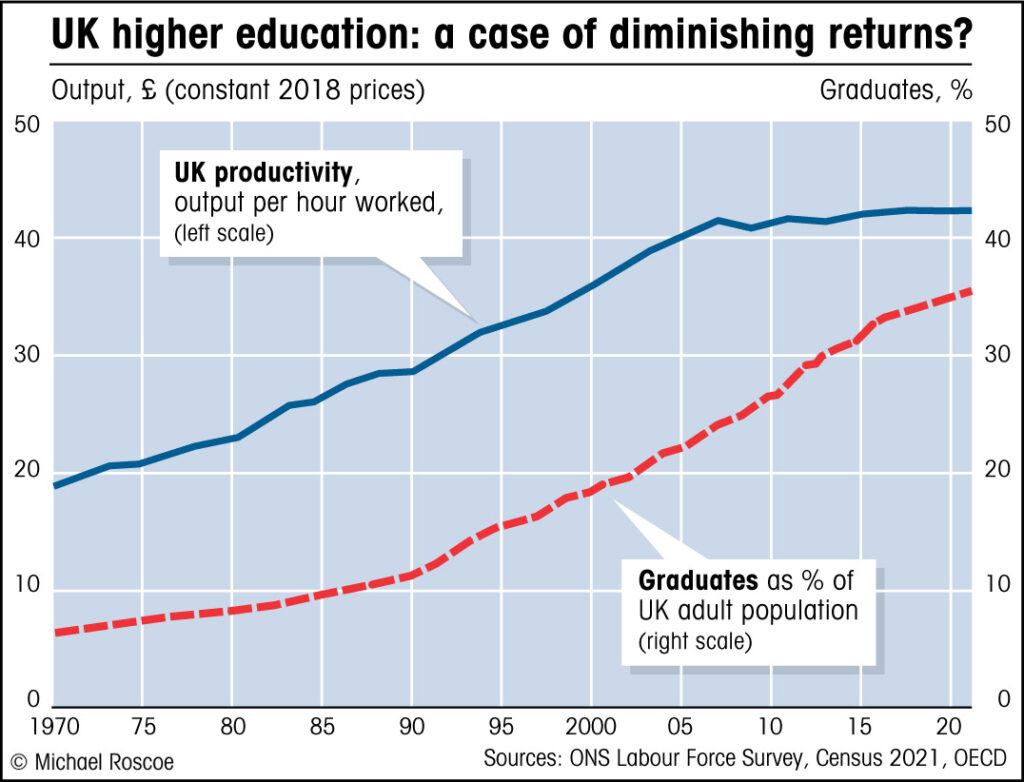

It has long been recognized that a well-educated workforce should benefit the nation, in particular by increasing the overall productivity of the economy. And the data in most countries does indeed show a rise in output per hour worked – the usual measure of productivity – corresponding with the rise in the number of graduates relative to total population, as seen in this chart for the UK.

There could of course be other factors driving the rise in productivity, such as the increasing automation of productive industry, especially agriculture and manufacturing. But this increase in automation is also partly due to the benefits of education acting on research and development, etc. It’s not easy to prove the effectiveness of higher education, but there is likely to be some benefit, up to a point, anyway.

In Britain’s case, however, we see that productivity has barely risen since the financial crisis of 2007-08, even though the number of graduates continues to rise quite rapidly. It appears that Britain has reached the point where graduates are no longer helping to raise productivity, and the likely reason for that is there are not enough opportunities to be found in productive employment. Hence we find that more people with a university-level education are taking jobs, predominantly in the service sector, that don’t make good use of their qualifications.

It must obviously be the case that there is a limit to the number of highly-qualified people that are needed in the workforce, and in Britain’s case we appear to have passed this limit. Other countries face a similar situation, but in more productive economies there is perhaps a better mix of college-level education and apprenticeships, etc, aimed more specifically at providing essential industrial skills.

See also: Britain’s Productivity Puzzle