Why is Britain suffering more than other advanced nations right now? Why has our economy taken an even bigger hit than the economies of other comparable countries?

The obvious answer to that question is Brexit, and undoubtably Britain’s exit from the European single market has played a big part, making trade with our biggest trading partner more difficult. But Brexit is not the whole story: we need to go back much further if we are to understand why Britain is getting poorer (and, indeed, why Brexit came about in the first place).

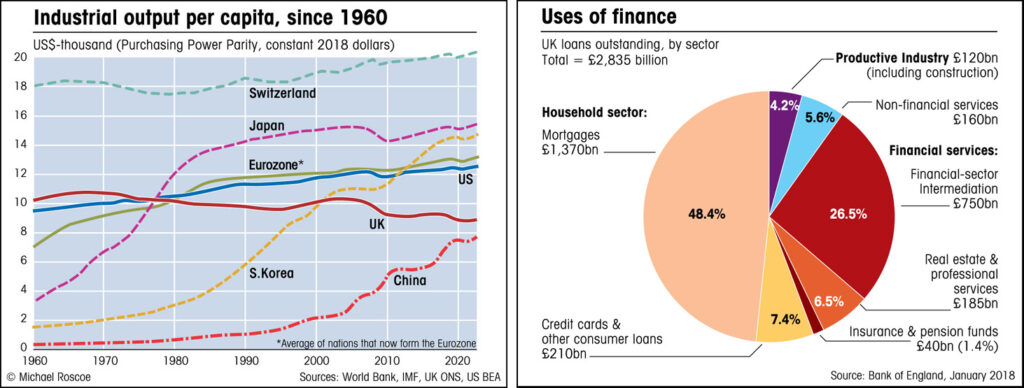

Why Britain is getting poorer, in two charts

For the majority of people in the world today, especially those in the more developed nations, life has been getting harder over the last few years. Even most economists would agree on that. There are several reasons for this, the most obvious being the Covid pandemic and the war caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, both of which have disrupted supplies and pushed up food and energy prices.

But there are less obvious reasons too, related to trends that began several decades ago.

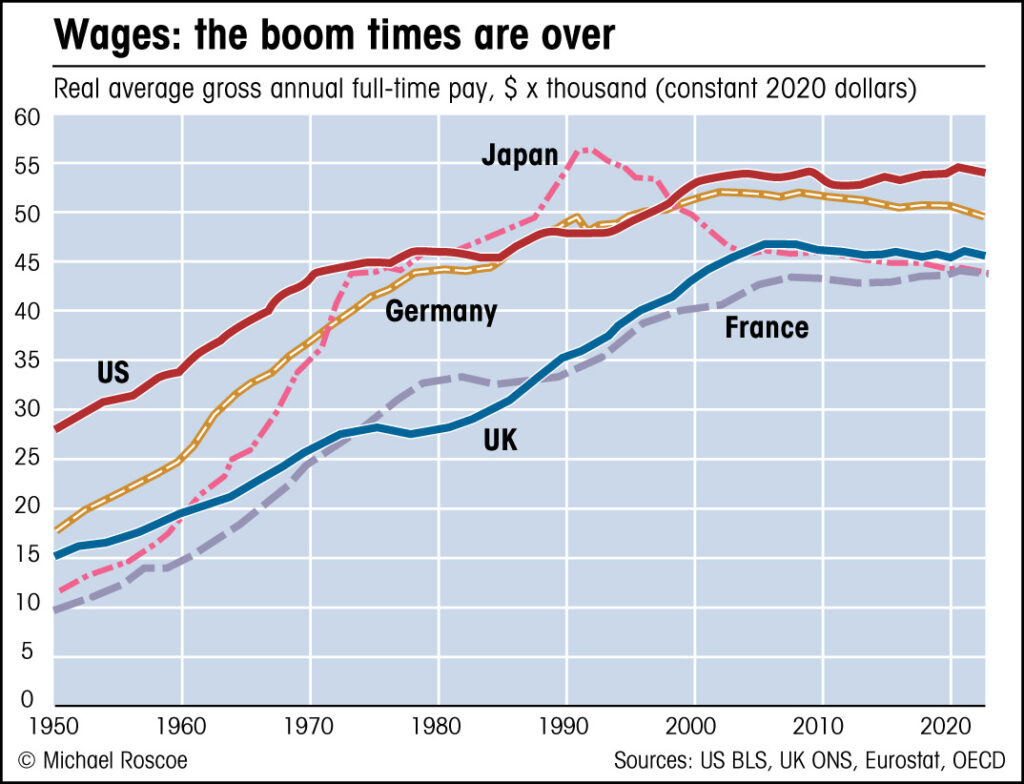

After the financial crash of 2008, I wrote a book, titled Why Things Are Going To Get Worse, (published in 2014 by New Internationalist), in which I explained why the postwar tendency towards increasing prosperity for the majority, which in most developed nations we had come to regard as the normal pattern of advancement – the international expansion of the ‘American Dream’, as it were – appeared to have run out of steam. I showed that, for most people, incomes were no longer rising, and might even be falling, in several of the more developed nations, especially Britain.

Although I failed to predict the Covid pandemic or the Ukraine war (or even Brexit!), the gist of my argument is still valid, and I think it provides some important insights into the problems we are experiencing today in Britain and, to a lesser extent, throughout the world generally. (The Institute for Fiscal Studies, for example, confirmed in November of 2022 that Britain is getting poorer.)

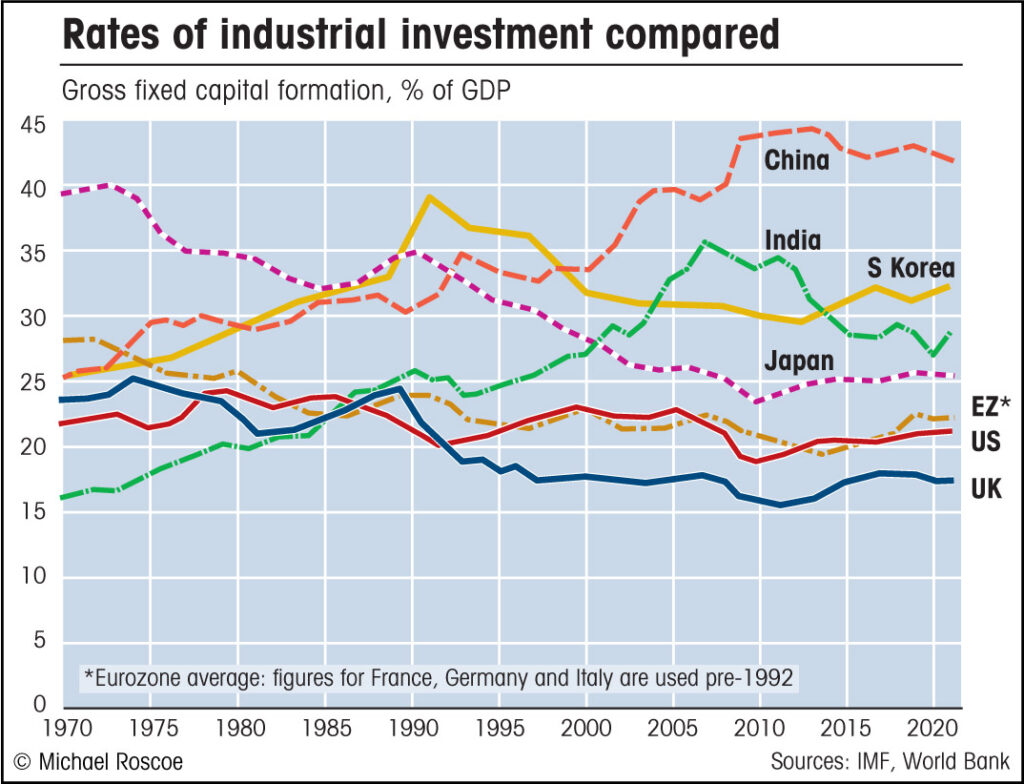

Following the Brexit vote in 2016, along with the US election of President Trump, I began writing a second book that focussed more specifically on what was really wrong with the Anglo-Saxon model of finance-dominated free-market capitalism. The gist of my argument is this: Britain, more than any other nation, is paying the price for decades of government policy that have prioritized financial services over productive industry. There is a sad irony here, in that a nation with one of the world’s biggest banking sectors has one of the lowest rates of real investment, by which I mean investment in productive industry.

There was a time, going back a century or two, when it was accepted by almost all economists, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx, that productive industry (ie, agriculture, mining, manufacturing and construction) created all the wealth, and that the service sector, while it could add value to production, was entirely dependent on this industrial wealth. That this must still be true (and I explain why it must be in my book) seems obvious to me, yet British policy over the last four decades, since the late 1970s, has favoured financial services to the detriment of real industry. This financialization and de-industrialization of the British economy has resulted, inevitably, in the UK becoming poorer.

The Anglo-Saxon model, which is also followed to a lesser extent by the US and various other countries, is geared towards making money through the appropriation of wealth produced elsewhere: from the oilfields of the Middle East; the factories of China and other lower-wage countries; the vast natural wealth of Russia that was captured by the oligarchs, and so on. The City of London, with its reputation for trustworthiness and its secretive links to offshore tax havens, attracts these funds, for various reasons (access to wider ‘investment’ opportunities, security from prying governments, anonymity, etc).

The two charts at the top of this page show two important (and related) aspects of Britain’s decline in prosperity: the deindustrialization of our economy, and the failure of the banking sector to invest in wealth-creating industry. I explain in more detail what these charts are showing here.

While most countries have increased their industrial output per capita over the past half-century (ie, economic value created by productive industry, relative to population), Britain is the only major economy in which such output has declined.

The effects of this reduction in UK wealth creation are now becoming obvious, even to most politicians and their advisers: for a long time they were masked by rising GDP figures. This is because GDP is boosted by debt-based spending and is a poor indicator of real wealth creation (as I explain here).

The problems caused by this relative reduction in British industrial production are compounded by the fact that an increasing proportion of the industry that does actually take place is now under foreign ownership, so a rising portion of the wealth still produced here in the UK ends up in the bank accounts of wealthy owners based abroad.

This is a result of the same failed policies that have prevailed in British politics over the past four decades or so: a simplistic over-reliance on the free-market process; the idea that the decisions made by market traders, acting in their own interests, will benefit the whole economy, if only governments will leave them alone.

The failure of this laissez-faire attitude is becoming more and more obvious, along with the associated problems of rising debt and inequality caused by the financialization of the economy. (By ‘financialization’, I mean the process by which financial services take priority over productive industry, in terms of government policy and the general focus of those in power.)

The solutions to these problems require an understanding of the relationships between work, wealth and money, because work (or ‘industry’) is the source of all wealth, and money is supposed to represent that wealth. This relationship has broken down in the financialized economy of today, because money can be created out of nothing, whereas real wealth takes work. The result of this breakdown is an increase in both debt and inequality: two related issues that play a big part in Britain’s decline.

I explain in my book how a relatively simple change to our monetary regime – the adoption of a sovereign money system – would help to reduce debt and inequality. We could replace our current unproductive model with one that promotes productive investment and makes it easier to fund useful projects, such as a green new deal. Instead of trying to make money from money, which is ultimately impossible and results only in the transfer of wealth from the real workers to those who are already wealthy, Britain could make more of the things that we really need, thus enriching the nation as a whole.

I have posted the Preface to my book here, and the Introduction here.